INVESTIGATIVE PROCESSES

Every architectural project is based on a specific site (or design problem) for which research and intervention are pursued in parallel. In pursuing any given architectural project we are reminded that architecture is primarily about design thinking expressed through drawing as a way of manifesting built form. Ideas, the basis of architectural exploration, are developed further through feedback and an iterative process. More and more, this iterative process is benefiting from investing in various media and techniques. For example, the use of mapping techniques photography, videography, simulation and narration. Whereas in their own right these are technical in nature, at the heart of it all is to make the process of architecture deeper and more meaningful in how it is conceived and later realised.

For that matter, as part of the ReSpace project, a nurturing approach was adopted as it creates a setting that encourages reflective practice, and supports a student’s individual development. Increasingly, a need to nurture future professionals is emerging, addressing what Weisman regards as a fundamental question for architectural education, which is ‘… not (about) how better to train future architects to compete against one another … but, rather how to improve the quality of architectural education and practice as inherently interrelated, life-affirming models for understanding the world at large, and each person’s belongingness to it’. This view embraces the idea of social justice, which we believe should be a core concern for architectural education, and influence the way we educate and nurture future architects.

Therefore, in collaboration with anthropology (UP), art (ADMA) and animation (BU) students and respective faculty, students of architecture and faculty of the University of Rwanda were immersed in an interdisciplinary exploration of the past, present and future of three sites (and people) through a series of mapping, drawing, reading, writing, reflective, audio and visual activities. These sites were selected for their history and current efforts to either enhance them (a memorial), relocate them (a school) or replan (an informal settlement). The outcome was more meaningful and alternative ways of viewing, knowing and disseminating the story of a place and its people.

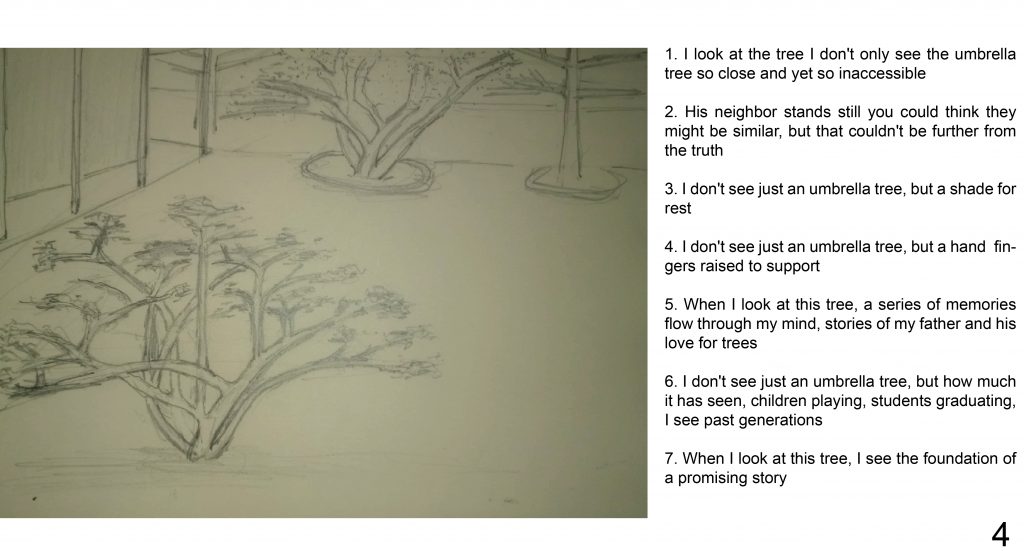

When writing about architectural theory, Robert Harbison (1998) echoes Wallace Stevens’s poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” In his poem Stevens uses thirteen short and separate sections that mention the blackbird in different ways. Each section evokes a feeling where “the thirteen word-pictures are a whole study of identity“. Like the poem, Harbison’s book creates a portrait of architecture in which “use, symbol, and metaphor coexist.” Architecture is connected to ‘Sculpture, Machines, the Body, Landscape, Models, Ideas, Politics, the Sacred, Subjectivity, and Memory’.

We take these ideas and developed a short exercise to create a portrait of a place that you can try in the Toolkit section.

1. Nóirín Hayes, ‘Teaching Matters in Early Educational Practice: The Case for a Nurturing Pedagogy’, Early Education and Development, 19.3 (2008), pp. 430-40.

2. Leslie Kanes Weisman, ‘Diversity by Design: Feminist Reflections on the Future of Architectural Education and Practice’, in The Sex of Architecture, ed. by Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996), pp. 273-86 (p. 273).

3. Robert, Harbison, Thirteen Ways: theoretical investigations in architecture, London: MIT Press, 1998.