whilst ‘places are considered to be materially real and temporally stable…their meanings are made and remade in the present. Places are not only continuously reinterpreted, they are haunted by past structures of meaning and material prescences from other times and lives’ (Till, 2005: 9)

ReSpace investigates how concepts of space/place, through arts-based participatory methods, can engage the ‘post-memory’ generation (Hirsch, 2008) in Rwanda and Kosovo to reimagine specific sites of memory and significance.

With partners from University of Rwanda, African Digital Media Academy, University of Prishtina, and AniBar, Bournemouth University worked on devising a project that saw collaboration with young people to explore a range of artistic methods in young people’s surroundings – these methods draw from anthropology, architecture and the arts, including animation and immersive technologies.

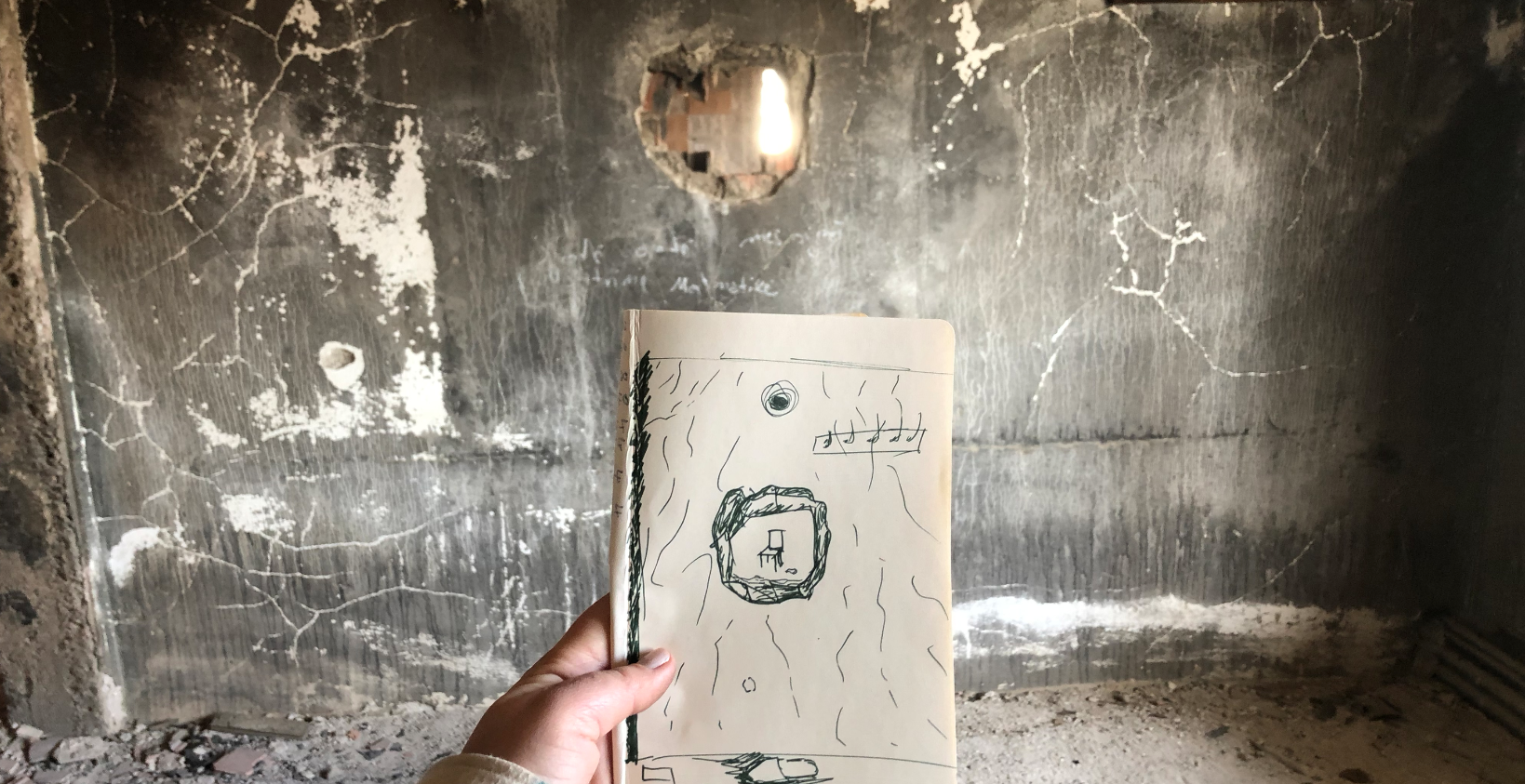

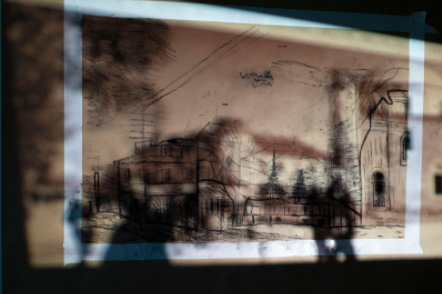

The project consisted of visiting places that were identified sites of interest in order to consider how a place bears witness to often-silenced, everyday histories of, for example, civic resistance and societal cohesion, before or after war and violence. By adopting the architectural concept of the ‘site survey’, young people used different methods to explore these spaces and reimagine them. The methods were connected to the project themes: Virtual Spaces, Past/Present Spaces, Designed Spaces, Reclaiming Future Spaces.

In Rwanda, the site visits took place in the wetlands of Kigali; the Gisimba Memorial Centre, La Colombiere School, and the local area of Mu Myembe were visited. During these visits young people took photos, 360 videos, sketches, interviewed locals, and made animations. These informed a collaboration with animation students in the UK to create a 3D interactive experience of these sites – seen as a means to engage in a reimagining of these places. The project combines immersive technologies with causal, factual (evidential, not selective) and affective approaches to history in contrast to essentializing stories of war horrors and victimisation.

In Kosovo, young people and artists visited the house school of Hertica and the Dodona theatre space to reflect upon the past as stories emerging from these places. Working alongside sound and visual artists, they considered ways of capturing and retelling the significance of these places and ways of looking at space. These served as interactive and exploratory civic educational means for youth to further an understanding of the histories of place.

ReSpace looks to the participatory engagement of young people in both artistic creative practice and research working in tandem. The project intends to impact upon educational content and methods in these countries and beyond.

Then and Now

Rwanda and former-Yugoslavia, Kosovo included, evoke imaginaries of violence that were results of a contemporary moment in media content and dissemination. Not only did news stories proliferate, but also documentary and artistic treatments of violence and carnage affected the public’s perception of narratives of space and place. In No Man’s Land, a film written and directed by Bosnian artist Danis Tanovic (2001 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film), amidst holding a position in the trenches, a Bosnian soldier, former school teacher reading the newspaper, releases an empathic sigh to news from Rwanda. “Shit in Rwanda”.

Similarities of experience, of history, and memory, leads us to raise questions about assumptions of pre-war and post-war social realities. As insiders to violence but outsiders to each others’ experiences, the project can enable discovery of new knowledge, exploring new methodologies, and empathetic learning.

Both countries experienced violent conflict and ethnic cleansing in the 1990s, as well as military and/or political international interventions, albeit different histories of colonialism and state authoritarianism, but largely re-defined the language of ethnic cleansing. Both conflicts also became sites of a documentary and artistic gaze, and often colliding representational regimes. Much of this has been produced in the Global North and disseminated to generate a flattened and often ahistorical understanding of root causes of violence that failed to account for structural legacies of colonialism.

Rwanda has often been described as experiencing a ‘post-conflict transformation from an agriculture-based economy to a knowledge-based one’, the effect of this made visible through the transformation of space in Kigali. The so-called socio-technological imaginaries of a

post-Genocide Rwanda (Bowman, 2017) encouraged by the state investment in ICT technologies has meant that schools such as ADMA (African Digital Media Academy) support the nation building drive that sees technology at the centre of these changes. The Vision 2020 State project sees Rwandan investment in the ICT sector, which this project supports.

This modernizing project is also spatially visible: In 2018, the iconic Kigali Convention Center won the prize for Best Architectural Design at the Africa Property Summit in South Africa, futuristic-looking and yet remembered for its conspicuous dome, reminiscent of the shape of traditional Rwandan huts. With studios such as Light Earth Design (with Peter Rich), MASS Design Group, Sharon Davis Design and Architectural Field Office all working within Rwanda, it is clear that architecture in the country is being fostered. As MASS have stated

“To acknowledge that architecture has this agency and power is to acknowledge that buildings, and the industry that erects them, are as accountable for social injustices as they are critical levers to improve the communities they serve.” (MASS, 2019)

A young generation of Rwandan architects being ushered by Christian Benimana have contributed to new narratives. The University of Rwanda, has a newly setup architecture department in its Faculty of Science and Technology.

In Kosovo, post-conflict state-building has seen the erection of institutions that aim for self-governance, albeit under continuous international multilateral oversight. The effects of this state-building on youth have largely remained unexplored, and even more so the radical transformation of cityscapes and urban spaces. Some weeks before his murder, Rexhep Luci, architect and head of urban planning for the capital Prishtina, remarked “All of whose who attack the city need to understand that the city will take vengeance one day” (Surroi 2000:

https://iwpr.net/global-voices/kosovo-tributes)

The Pandemic interrupted the original project plans for young people to travel, meet and learn from each other in person across continents, between Kosovo and Rwanda, from early 2020 onwards. For many of the young participants, these travel opportunities had been a major incentive to join, particularly considering the existing limitations on travel for young people in Kosovo and Rwanda because of economic, visa and other restrictions. It also created a specific problem, how does one understand a place from a distance?

Whilst the young people were able to visit sites in their respective home country, how could they share this with other young people? Interactions were for the most part limited to online chats on Zoom, and the digital sharing of audio-visual material, video diaries and soundscapes. But the impressions of these places were unfortunately mostly understood in a fragmentary manner.

We began to look at other modes of interaction, such as using InstaLive sessions to talk to people present, viewing and sharing 360 video, and using VR headsets as an opportunity to arrive at a fuller experience of place from a distance. In doing so we were able to share each other’s exploration of space and place – the social and physical surroundings in Kigali or Prishtina.

‘It seems historically inevitable that we will leave behind the nostalgic notion of a site and identity as essentially bound to the physical actualities of a place. Such a notion, if not ideologically suspect, is at least out of sync with the prevalent description of contemporary life as a network of unanchored flows.’ (Kwon, 2004:164)

When Miwon Kwon (2004) wrote about so-called site-specific art and the deterritorialization of the site they described the liberating effect of a fluid ‘migratory’ model [as described by Delueze and Guattari]. This discussion took place in a context where transnational movement, across and between different sites came with such ease in a pre-Covid-19 pandemic world. Notwithstanding this, Kwon argued there is a continued and deep rooted psychological connection to a place that endures and informs our identities – the ‘phantom of a site’.

As ReSpace straddled a pre and post-pandemic timeline, it had to contend with a shift from a positivist view of the fluid connections that could emerge from our visits to Rwanda, Kosovo and the UK, to the reality that the physical actuality of a place will only be experienced by a few in situ. Experiencing a nostalgia for a place never visited was mitigated by the sharing of personal experiences, a form of storytelling from young people who rediscovered these sites and recounted to others their own impressions of these places.